|

Guideposts

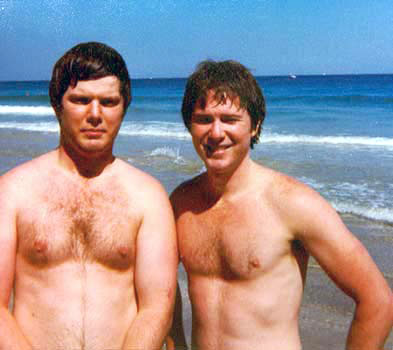

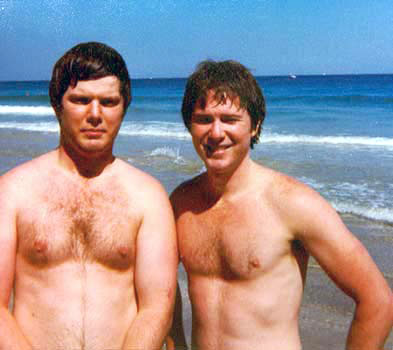

Emmett and Steve -Theirs

is an amazing

story of unconditional love and sacrifice.

Brothers

June 1973:

On a weekend at the New Jersey Shore, the car driven by 18-year-old

Emmett - my next brother down in our family of five boys and a girl

- was hit and totally demolished by  a

car driven by a teenager who'd been drinking. The police told us Emmett

was dead. Then doctors located a faint heartbeat. Injuries to Emmett's

body were confined to a broken collarbone and lacerated left arm. But

you couldn't see the severest damage. It was inside his head - in his

brain - causing what the physicians call "a persistent vegetative

state". Coma. a

car driven by a teenager who'd been drinking. The police told us Emmett

was dead. Then doctors located a faint heartbeat. Injuries to Emmett's

body were confined to a broken collarbone and lacerated left arm. But

you couldn't see the severest damage. It was inside his head - in his

brain - causing what the physicians call "a persistent vegetative

state". Coma.

The first time I saw Emmett in the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia,

I fainted. His big, six foot frame was strung with tubes, and a clear

plastic globe around his head sprouted wires that reported his vital

signs to a computer. He lay on a ice blanket, and the blend of cold

and warm air enveloped him in an eerie fog.

Emmett had just graduated from high school, and I - four years younger

- had just graduated from Notre Dame. A few days earlier I'd started

a job to earn money for a trip to Europe. I felt I needed to get away

from my family - from the familiar - and do some serious thinking about

my goals in life. But Emmett's deathlike state filled my mind. He couldn't

walk, talk, drink, eat, see, or think. He was alive only because a machine

was breathing for him.

Day after day my family and I kept a vigil in the Intensive Care Unit.

Emmett's girl friend Diane, an attractive high school senior, was usually

with us. Emmett just lay there, unaware, unmoving. The only thing we

could for him was pray and we did plenty of that.

In the hour's drive back and forth to the hospital from our home in

Haddonfield, New Jersey, my father would start a prayer. Then we would

take turns praying aloud, or we pray in unison. We prayed at home or

at church, and so did our friends. We prayed not only for Emmett, but

also for ourselves - for the strength to keep striving and hoping in

the face of a grave prognosis.

At last, on the 15th day, the doctors told us Emmett was responding

- just barely - when his hand was squeezed. That was all my father needed.

He grabbed Emmett's left hand. "Emmett," he said in a choked

voice, "we're praying so hard for you. Can you pray and fight back?

Squeeze my hand if you can."

He paused, then turned to the rest of us. "He squeezed my hand.

He really squeezed. He wants to fight and pray to come back, and each

of us is going to help. We'll keep on fighting and praying with him."

Maybe Emmett squeezed and maybe he didn't. After several tries to get

him to respond to me, I wasn't convinced. But the next day Emmett did

something that broke throw my skepticism. I was holding a telephone

to his ear while our four-year-old brother Kevin, who hero-worshipped

him, bombarded him with questions. "Emmett? You know how you always

tell me 'hang in there'? Remember that, Emmett? I miss you. When will

you come home? Soon, Emmett?"

I looked down at Emmett's masklike face. His cheeks were wet with tears.

I didn't realize it at the time, but at that moment I committed myself

to Emmett, to reclaiming him mentally and physically. Good-bye summer

job. Good-bye Europe. Good-bye independence. The battle to save Emmett's

life was about to consume two years of my life.

July 1973: The

next day I had my first disagreement with the medical establishment.

The doctor was shaking his head. "I doubt those were tears. His

eyes were watering. That often happens with people in a coma."

"Those were tears. I'm sure of it."

"You know, Steve, imagination is a powerful force when you want

very much to believe something.

"Doctor, I cut him off, "Emmett's a stranger to you. But I

know my brother's a fighter. As long as there's a breath in him, the

guy will not give up. I think he can make it back."

"I don't believe you understand how bad his situation is. Mentally

he's almost a blank."

I nodded - and found myself outlining my new "fight" strategy.

I understand that, Doctor. It's as though Emmett has a hundred miles

to go and we have to help him an inch at a time. But after yesterday

I'm positive he has some awareness - enough for us to work with. If

we can only build that up enough so Emmett catches on to what's expected

of him, he'll fight back with us."

The opening move in my campaign was finding out as much as I could about

coma, as fast as possible. From doctors and material I read in the library

I learned that Emmett needed stimulation. Massive doses of it. Yet at

the same time he needed to sleep a lot. I decided to try stimulating

him an hour at a time, then giving him an hour's rest. When I mentioned

my plan to Emmett's girlfriend Diane, she offered to help me.

A

month after the accident, when Emmett was released from the Intensive

Care Unit to round-the-clock private-duty nurses, Diane and I started

our work. It was grueling. For an hour we'd talk to Emmett about what

was happening at home, how everybody was asking about him. When one

of us ran out of small talk, the other took over. After an hour, we

would put a cassette of quiet music in Diane's tape player. After 60

minutes of that, we would read from current magazines, play lively music

and sing, clap our hands and tap our feet. Meanwhile, twice a day, a

physical therapist gave Emmett passive exercises, pushing and pulling

his arms, legs, fingers and toes. She taught us how to do the movements,

and we repeated them another two or three times a day. A

month after the accident, when Emmett was released from the Intensive

Care Unit to round-the-clock private-duty nurses, Diane and I started

our work. It was grueling. For an hour we'd talk to Emmett about what

was happening at home, how everybody was asking about him. When one

of us ran out of small talk, the other took over. After an hour, we

would put a cassette of quiet music in Diane's tape player. After 60

minutes of that, we would read from current magazines, play lively music

and sing, clap our hands and tap our feet. Meanwhile, twice a day, a

physical therapist gave Emmett passive exercises, pushing and pulling

his arms, legs, fingers and toes. She taught us how to do the movements,

and we repeated them another two or three times a day.

We worked with Emmett 12 hours a day for six straight days. He remained

unchanged. Once in a while he'd give a weak little squeeze when we urged

him, but most times not. Another day went by and another. Emmett's brown

eyes were open a little more than they had been - they were dull and

glazed but open.

One day, when my parents came into the room, I noticed that Emmett's

eyes moved toward the sound. I told my mother and she rushed to the

bedside and held on to Emmett. "Do you know me, Emmett? Do you

recognize me? Tell me, Emmett!"

A rasping groan came from deep down inside him: "Mmmmmmmomm."

August 1973:

Now, Diane

and I became teachers. Demanding ones. Emmett was unwilling - or unable

- to speak again, but we got him to "talk" to us with his

left hand (his right side was paralyzed). We asked him questions he

could answer with his fingers - one for yes, two for  no. no.

"Is your sister named Sue, Emmett?" One finger.

"Am I your brother Kevin?" Two fingers.

"Emmett, you and I and Diane are here. How many people is that?"

Three fingers.

Meanwhile, we were delving deeper into prayer. My father joined a special

prayer group. My mother had decided that since Emmett had so many physical

problems she would pray for one improvement at a time. She began by

praying specifically for his eyesight.

On August 18, holding four fingers in front of his face, Mother asked

Emmett, "How many fingers do you see?"

Slowly his fingers moved - one, two, three, four!

After that, Emmett began to see a tiny bit better every day.

Now and then we were able to get him to say a few one-syllable words,

but he did nothing on hid own. Never spoke, never responded, never responded,

never ate, drank or moved unless we urged him.

September 1973:

With somber warnings not to let our expectations rise too high, the

doctors allowed us to transfer Emmett to a rehabilitation center where

trained therapists could concentrate on trying to improve his speech

and physical movement. The medical word that frightened Diane and me

most was "plateau." It meant that Emmett's progress could

flatten out at any time - get to a certain level and never go any further.

Our fears worsened after Emmett had been at the rehab center a few days.

Diane and I were the only two people who had been observing him constantly

and minutely 12 hours a day for over a month - and we believed that

the routine therapy he was getting was not adequate. In fact, it was

clear to us that no center anywhere could provide the

extra effort he needed to keep from deteriorating or plateauing. He

had to have all-day every-day, one-on-one therapy.

So Diane and I decided to supply that extra effort ourselves. The center

finished working with Emmett at 4:00 p.m. each day. From 4:00 to 10:00

p.m. during daily visiting hours, we would take over.

I'd learned a lot about weight lifting and other kinds of physical conditioning

while earning my black belt in karate. A physical therapist at the hospital

had shown me how to work with Emmett using parallel bars to help him

stand up and mat exercises for sit-ups to build his muscle strength.

Diane's job was to supplement the work of the speech therapist. Emmett

had aphasia; his ability to use words correctly had damaged. The part

of his brain that recognized objects had lost contact with the part

that named them. Diane held up various objects for Emmett to identify,

corrected him when he was wrong - which was almost always - and encouraged

him at the same time. "You're mixed up on the name of things, Emmett.

Working with me will help straighten you out. Want to try again?"

During the hours we worked with Emmett we prayed for small gains - for

one more sit-up, one more step using the support bars, one more sign

of word-recognition. And we thanked God for the least little sign of

progress.

October 1973:

A new problem. Emmett got a staph infection - a liability of prolonged

hospital stays. But once over that hurdle, our inch-by-inch progress

continued. By now Emmett's neck muscles were strong enough to keep his

head from lolling to the side if it wasn't strapped in place, and he

learned to feed himself and kick his paralyzed right leg a little when

we asked him to. Since he could now hold his torso erect in a wheelchair,

we began taking Emmett outside.

On his first outing Emmett heaved himself forward to pull up a few blades

of grass, to feel the earth he'd been away from so long. But that hopeful

sign was wiped out a few weeks later.

Diane was showing Emmett a picture of a house. "Can you name this?"

"Hous-hou-Howard Johnson."

We all laughed, including Emmett. Except that he went on and on, out

of control, and it was an idiot's laugh.

The doctor explained that when the parts of the brain that control the

emotion system are damaged, the patient's reaction may be overblown.

No telling how long the symptom would last.

We hoped it would go away soon, but it didn't. From then on, it happened

at least two or three times a day.

November 1973:

The better I got at working out with Emmett, the more convinced I became

that he should be brought home where our family could focus on stimulating

him mentally and physically all the time. He was still only half-awake,

someone who looked - and acted - both crippled and retarded.

Also, Emmett was in constant pain from the irritation of the urinary

catheter he'd worn since the accident. The rehab center could do little

to help him develop bladder control - that would take constant supervision,

day and night. At home, I could give him that.

At first my parents were afraid of the responsibility of having Emmett

at home. But after praying and a few trial visits on weekends they felt

more secure. The day before Thanksgiving Emmett came home.

We put Emmett's bed in an alcove off the living room, and I slept on

a cot beside him so he could wake me whenever he needed me. I'd located

a health spa where he could work out, and my mother had found a speech

pathologist. She also hired people to tutor him in math and English.

Although Diane had a lesser role to play with Emmett, she visited and

kept him company faithfully, something that most people outside the

family didn't feel comfortable about doing for more than a few minutes

at a time.

Our next goal was to get him to take steps without the support of the

parallel bars. We had exercised the atrophied muscles on his paralyzed

right side enough to achieve some movement. Now the obstacle was his

lack of balance. He couldn't take more than a step or two without falling

down.

I had no idea what to do about that. To complicate matters, I was beginning

to feel impatient and defeated about Emmett's slow progress. Meanwhile,

my own time to travel and begin a career was passing by.

I must have shown my frustration because one day my mother took me aside.

"What's the matter, Steve?"

"Nothing special."

"I know better. Tell me about it."

"Oh, I'm just discouraged, I guess. Sometimes I think I'm wasting

my time. That no matter how I try, Emmett will never be able to walk."

My mother took hold of my shoulders.

"Never say that. He will walk. Because you're going

to help him."

I don't know if it was her conviction or the challenge or foolish pride

or sentiment. But I heard myself saying something incredible. "You're

right, Mom. And my Christmas present to you is going to be Emmett walking."

It was more than incredible. It was crazy. How could Emmett walk if

he couldn't regain his balance?

What happened next is an example of the leading we felt we were getting

from God.

December 1973:

I was visiting a friend and his wife and their three year-old son, watching

the baby crawl on the floor and pull himself up, holding on to chairs

and tables.

"See that?" his mother remarked. "Any day now he'll start

taking steps and then he'll be walking instead of crawling."

That was it! Crawling was what Emmett needed to do to help get back

his balance - and his confidence - back. The very next day my mother

and I began teaching him to crawl. We worked on his paralyzed side while

Emmett coordinated the movements of his left arm and leg. Right arm

forward, left leg forward. Left arm forward, right leg forward.

After practicing 20 minutes morning, noon and night for two weeks, Emmett

was crawling - not fast or smoothly, but crawling. At the spa we had

a program of chin-ups, knee bends, swimming and working with a shoulder

wheel and a stationary bike (I had to tie Emmett's right foot to the

pedal till he could keep it in place on his own). When Emmett's knees

got sore from crawling I bought him knee pads - and also a quad cane

which has a four-prong base. One day, with his left hand grasping the

cane and me holding the back of his belt, Emmett took his first lurching

step. Christmas was only a week away.

Emmett worked earnestly, wobbling, tottering forward with the quad cane,

relying on me to steady him with a hand on his shoulder. As he struggled,

I noticed a frown wrinkle his face now and then. I wondered about it.

He hadn't shown emotion for such a long time. When I mentioned it to

a pathologist, though, he was negative. "That doesn't mean he feels

anything - it's just a reflex."

Christmas morning came. After all the family's presents had been opened

and the wrappings cleared away, I gave my mother an envelope and pushed

Emmett's wheelchair around the hallway.

I hear her read the message to the others. "Merry Christmas, Mom.

Look who's coming. With love from Steve."

In the hallway, I helped Emmett stand up and get set with the quad cane.

"Okay, now, slow and careful does it. Keep your mind on what you're

doing. You know what this means to Mom."

With a nod, Emmett began his journey. One foot in front of the other,

wavering, recovering. Now he was in the entrance of the living room,

where everyone sat frozen, silent, watching.

Halfway across the room he began to sway. I steadied him with a hand

on his shoulder. One more step. Another. Another. Three steps to Mom.

Now two. Now one.

He stood in front of her.

My mother wrapped her arms around him and my father hugged them both.

I stared at Emmett. His eyes were still glazed, but something shone

from them that was clearly recognizable. Pride.

January 1974

- and After: Emmett's triumphant walk came six months after

the accident. Another year and a half would go by before I felt free

to go back to my own life, to work on a career or even to think about

having a girlfriend. I' discovered that I was too involved - some said

"obsessed" - with Emmett to put any substance into any other

kind of relationship.

As for Emmett, there was no point where he "turned a corner"

and was suddenly all right again. It continued to be a matter of adding

on - bit by bit, inch by inch, day by day. Eventually he could crawl

up and down stairs... had better breath pressure, controlled his bladder

eight hours at a time... was able to use an ordinary cane, then walk

unaided. The idiot laugh disappeared. He climbed the stairs. Little

signs showed his volition was coming back. He'd be the first one to

say "Hello". Or he'd turn off radio music he didn't like.

His flat, monotonous speech gained rhythm and tone.

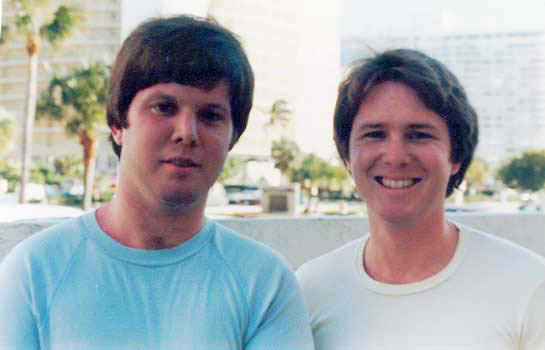

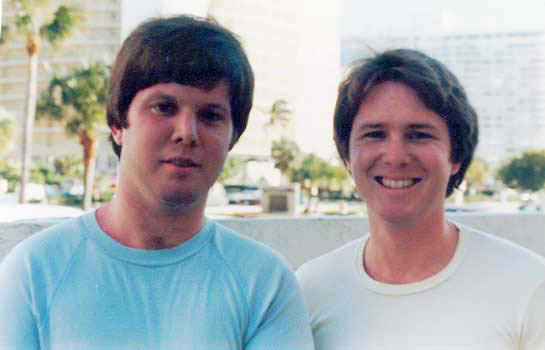

Now, more than 10 years later, many changes have come to Emmett, Diane,

and me. Gradually, Diane began to resume a life independent of Emmett.

In time she married and had two children. I moved to New York and took

up a career as an actor and writer. After undergraduate work at Millsaps

College, Emmett settled in Florida. Apart from a slight residual weakness

on his right side, he's perfectly well, able to work, and as I write

this, he's planning to marry a delightful young woman who adores him.

Today, some people who hear about Emmett's recovery call it a miracle.

I resent that. Miracles are supernatural. This wasn't. Reclaiming Emmett's

life was a human battle, carried on with intensive, monotonous, stubborn

persistence by my family and Diane and me. We're ordinary people and

we overcame fear and pessimism and poor odds and even cold facts by

concentrating totally on hard work and the most natural thing in the

world - prayer.

I'm not saying that every desperate coma case will respond to a massive

family effort the way Emmett did. Coma therapy is a young science; research

and clinical experience are limited. Time and time again, the doctors

told us, "Don't get your hopes up."

But what if we hadn't?

Top

|

a

car driven by a teenager who'd been drinking. The police told us Emmett

was dead. Then doctors located a faint heartbeat. Injuries to Emmett's

body were confined to a broken collarbone and lacerated left arm. But

you couldn't see the severest damage. It was inside his head - in his

brain - causing what the physicians call "a persistent vegetative

state". Coma.

a

car driven by a teenager who'd been drinking. The police told us Emmett

was dead. Then doctors located a faint heartbeat. Injuries to Emmett's

body were confined to a broken collarbone and lacerated left arm. But

you couldn't see the severest damage. It was inside his head - in his

brain - causing what the physicians call "a persistent vegetative

state". Coma. A

month after the accident, when Emmett was released from the Intensive

Care Unit to round-the-clock private-duty nurses, Diane and I started

our work. It was grueling. For an hour we'd talk to Emmett about what

was happening at home, how everybody was asking about him. When one

of us ran out of small talk, the other took over. After an hour, we

would put a cassette of quiet music in Diane's tape player. After 60

minutes of that, we would read from current magazines, play lively music

and sing, clap our hands and tap our feet. Meanwhile, twice a day, a

physical therapist gave Emmett passive exercises, pushing and pulling

his arms, legs, fingers and toes. She taught us how to do the movements,

and we repeated them another two or three times a day.

A

month after the accident, when Emmett was released from the Intensive

Care Unit to round-the-clock private-duty nurses, Diane and I started

our work. It was grueling. For an hour we'd talk to Emmett about what

was happening at home, how everybody was asking about him. When one

of us ran out of small talk, the other took over. After an hour, we

would put a cassette of quiet music in Diane's tape player. After 60

minutes of that, we would read from current magazines, play lively music

and sing, clap our hands and tap our feet. Meanwhile, twice a day, a

physical therapist gave Emmett passive exercises, pushing and pulling

his arms, legs, fingers and toes. She taught us how to do the movements,

and we repeated them another two or three times a day. no.

no.